Bessel function

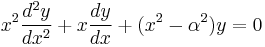

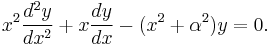

In mathematics, Bessel functions, first defined by the mathematician Daniel Bernoulli and generalized by Friedrich Bessel, are canonical solutions y(x) of Bessel's differential equation:

for an arbitrary real or complex number α (the order of the Bessel function); the most common and important cases are for α an integer or half-integer.

Although α and −α produce the same differential equation, it is conventional to define different Bessel functions for these two orders (e.g., so that the Bessel functions are mostly smooth functions of α). Bessel functions are also known as cylinder functions or cylindrical harmonics because they are found in the solution to Laplace's equation in cylindrical coordinates.

Applications of Bessel function

Bessel's equation arises when finding separable solutions to Laplace's equation and the Helmholtz equation in cylindrical or spherical coordinates. Bessel functions are therefore especially important for many problems of wave propagation and static potentials. In solving problems in cylindrical coordinate systems, one obtains Bessel functions of integer order (α = n); in spherical problems, one obtains half-integer orders (α = n + ½). For example:

- Electromagnetic waves in a cylindrical waveguide

- Heat conduction in a cylindrical object

- Modes of vibration of a thin circular (or annular) artificial membrane (such as a drum or other membranophone)

- Diffusion problems on a lattice

- Solutions to the radial Schrödinger equation (in spherical and cylindrical coordinates) for a free particle

- Solving for patterns of acoustical radiation

Bessel functions also have useful properties for other problems, such as signal processing (e.g., see FM synthesis, Kaiser window, or Bessel filter).

Definitions

Since this is a second-order differential equation, there must be two linearly independent solutions. Depending upon the circumstances, however, various formulations of these solutions are convenient, and the different variations are described below.

Bessel functions of the first kind : Jα

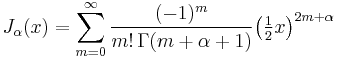

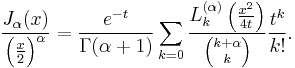

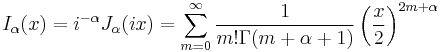

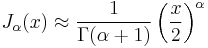

Bessel functions of the first kind, denoted as Jα(x), are solutions of Bessel's differential equation that are finite at the origin (x = 0) for integer α, and diverge as x approaches zero for negative non-integer α. The solution type (e.g., integer or non-integer) and normalization of Jα(x) are defined by its properties below. It is possible to define the function by its Taylor series expansion around x = 0:[1]

where Γ(z) is the gamma function, a generalization of the factorial function to non-integer values. The graphs of Bessel functions look roughly like oscillating sine or cosine functions that decay proportionally to 1/√x (see also their asymptotic forms below), although their roots are not generally periodic, except asymptotically for large x. (The Taylor series indicates that −J1(x) is the derivative of J0(x), much like −sin x is the derivative of cos x; more generally, the derivative of Jn(x) can be expressed in terms of Jn±1(x) by the identities below.)

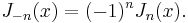

For non-integer α, the functions Jα(x) and J−α(x) are linearly independent, and are therefore the two solutions of the differential equation. On the other hand, for integer order α, the following relationship is valid (note that the Gamma function becomes infinite for negative integer arguments):[2]

This means that the two solutions are no longer linearly independent. In this case, the second linearly independent solution is then found to be the Bessel function of the second kind, as discussed below.

Bessel's integrals

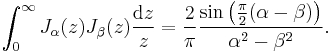

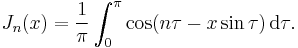

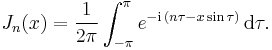

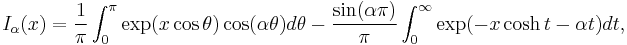

Another definition of the Bessel function, for integer values of  , is possible using an integral representation:

, is possible using an integral representation:

Another integral representation is:

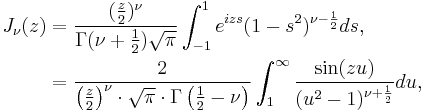

This was the approach that Bessel used, and from this definition he derived several properties of the function. The definition may be extended to non-integer orders by (for  )

)

or for  by

by

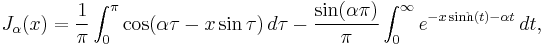

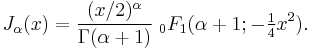

Relation to hypergeometric series

The Bessel functions can be expressed in terms of the generalized hypergeometric series as

This expression is related to the development of Bessel functions in terms of the Bessel–Clifford function.

Relation to Laguerre polynomials

In terms of the Laguerre polynomials  and arbitrarily chosen parameter

and arbitrarily chosen parameter  , the Bessel function can be expressed as[7]

, the Bessel function can be expressed as[7]

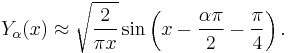

Bessel functions of the second kind : Yα

The Bessel functions of the second kind, denoted by Yα(x), are solutions of the Bessel differential equation. They have a singularity at the origin (x = 0).

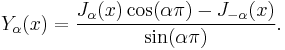

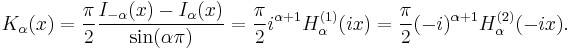

Yα(x) is sometimes also called the Neumann function, and is occasionally denoted instead by Nα(x). For non-integer α, it is related to Jα(x) by:

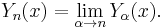

In the case of integer order n, the function is defined by taking the limit as a non-integer α tends to 'n':

There is also a corresponding integral formula (for  ),[8]

),[8]

Yα(x) is necessary as the second linearly independent solution of the Bessel's equation when α is an integer. But Yα(x) has more meaning than that. It can be considered as a 'natural' partner of Jα(x). See also the subsection on Hankel functions below.

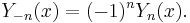

When α is an integer, moreover, as was similarly the case for the functions of the first kind, the following relationship is valid:

Both Jα(x) and Yα(x) are holomorphic functions of x on the complex plane cut along the negative real axis. When α is an integer, the Bessel functions J are entire functions of x. If x is held fixed, then the Bessel functions are entire functions of α.

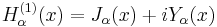

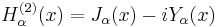

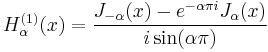

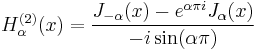

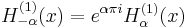

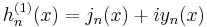

Hankel functions: Hα(1), Hα(2)

Another important formulation of the two linearly independent solutions to Bessel's equation are the Hankel functions Hα(1)(x) and Hα(2)(x), defined by:[9]

where i is the imaginary unit. These linear combinations are also known as Bessel functions of the third kind; they are two linearly independent solutions of Bessel's differential equation. They are named after Hermann Hankel.

The importance of Hankel functions of the first and second kind lies more in theoretical development rather than in application. These forms of linear combination satisfy numerous simple-looking properties, like asymptotic formulae or integral representations. Here, 'simple' means an appearance of the factor of the form  . The Bessel function of the second kind then can be thought to naturally appear as the imaginary part of the Hankel functions.

. The Bessel function of the second kind then can be thought to naturally appear as the imaginary part of the Hankel functions.

The Hankel functions are used to express outward- and inward-propagating cylindrical wave solutions of the cylindrical wave equation, respectively (or vice versa, depending on the sign convention for the frequency).

Using the previous relationships they can be expressed as:

if α is an integer, the limit has to be calculated. The following relationships are valid, whether α is an integer or not:[10]

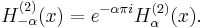

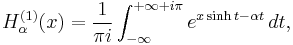

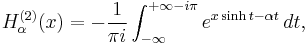

The Hankel functions admit the following integral representations for  :[11]

:[11]

where the integration limits indicate integration along a contour that can be chosen as follows: from −∞ to 0 along the negative real axis, from 0 to ±iπ along the imaginary axis, and from ±iπ to +∞±iπ along a contour parallel to the real axis.[12]

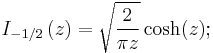

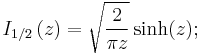

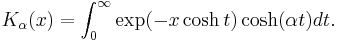

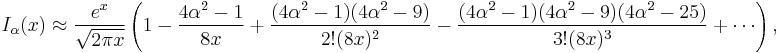

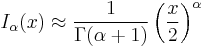

Modified Bessel functions : Iα, Kα

The Bessel functions are valid even for complex arguments x, and an important special case is that of a purely imaginary argument. In this case, the solutions to the Bessel equation are called the modified Bessel functions (or occasionally the hyperbolic Bessel functions) of the first and second kind, and are defined by any of these equivalent alternatives:[13]

These are chosen to be real-valued for real and positive arguments x. The series expansion for Iα(x) is thus similar to that for Jα(x), but without the alternating (−1)m factor.

Iα(x) and Kα(x) are the two linearly independent solutions to the modified Bessel's equation:[14]

Unlike the ordinary Bessel functions, which are oscillating as functions of a real argument, Iα and Kα are exponentially growing and decaying functions, respectively. Like the ordinary Bessel function Jα, the function Iα goes to zero at x = 0 for α > 0 and is finite at x = 0 for α = 0. Analogously, Kα diverges at x = 0.

Two integral formulas for the modified Bessel functions are (for  ):[15]

):[15]

Modified Bessel functions  and

and  can be represented in terms of rapidly converged integrals[16]

can be represented in terms of rapidly converged integrals[16]

The modified Bessel function of the second kind has also been called by the now-rare names:

- Basset function

- Modified Bessel function of the third kind

- Modified Hankel function[17]

- MacDonald function

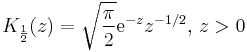

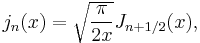

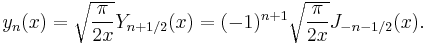

Spherical Bessel functions: jn, yn

When solving the Helmholtz equation in spherical coordinates by separation of variables, the radial equation has the form:

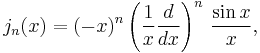

The two linearly independent solutions to this equation are called the spherical Bessel functions jn and yn, and are related to the ordinary Bessel functions Jn and Yn by:[18]

is also denoted

is also denoted  or ηn; some authors call these functions the spherical Neumann functions.

or ηn; some authors call these functions the spherical Neumann functions.

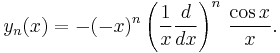

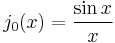

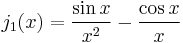

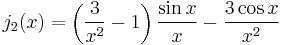

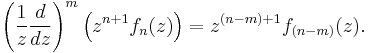

The spherical Bessel functions can also be written as (Rayleigh's Formulas):[19]

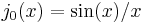

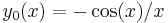

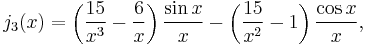

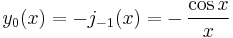

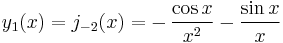

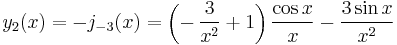

The first spherical Bessel function  is also known as the (unnormalized) sinc function. The first few spherical Bessel functions are:

is also known as the (unnormalized) sinc function. The first few spherical Bessel functions are:

and

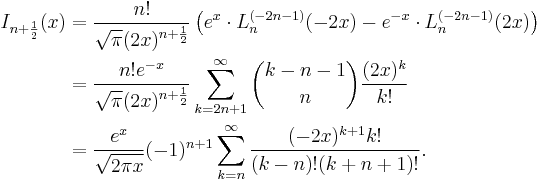

The general identities are

(the upper limit of summation is understood to be the largest integer less than or equal to (n+1)/2); a closed form employing Laguerre's polynomial  (cf. Bessel's polynomial) and other representations are provided by

(cf. Bessel's polynomial) and other representations are provided by

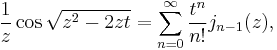

Generating function

The spherical Bessel functions have the generating functions [22]

Differential relations

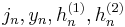

In the following  is any of

is any of  for

for

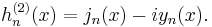

Spherical Hankel functions: hn

There are also spherical analogues of the Hankel functions:

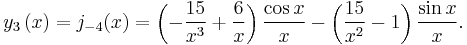

In fact, there are simple closed-form expressions for the Bessel functions of half-integer order in terms of the standard trigonometric functions, and therefore for the spherical Bessel functions. In particular, for non-negative integers n:

and  is the complex-conjugate of this (for real

is the complex-conjugate of this (for real  ). It follows, for example, that

). It follows, for example, that  and

and  , and so on.

, and so on.

The spherical Hankel functions appear in problems involving spherical wave propagation, for example in the multipole expansion of the electromagnetic field.

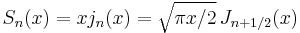

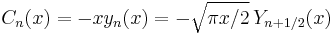

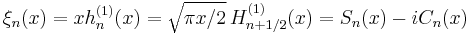

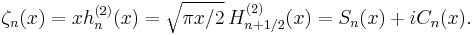

Riccati–Bessel functions: Sn, Cn, ξn, ζn

Riccati–Bessel functions only slightly differ from spherical Bessel functions:

They satisfy the differential equation:

This differential equation, and the Riccati–Bessel solutions, arises in the problem of scattering of electromagnetic waves by a sphere, known as Mie scattering after the first published solution by Mie (1908). See e.g., Du (2004)[24] for recent developments and references.

Following Debye (1909), the notation  is sometimes used instead of

is sometimes used instead of  .

.

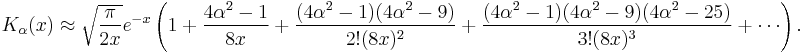

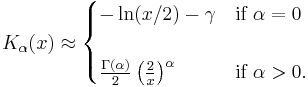

Asymptotic forms

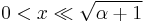

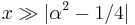

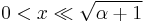

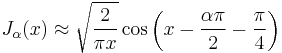

The Bessel functions have the following asymptotic forms for non-negative α. For small arguments  , one obtains:[25]

, one obtains:[25]

where  is the Euler–Mascheroni constant (0.5772...) and

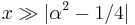

is the Euler–Mascheroni constant (0.5772...) and  denotes the gamma function. For large arguments

denotes the gamma function. For large arguments  , they become:[25]

, they become:[25]

(For α=1/2 these formulas are exact; see the spherical Bessel functions above.) Asymptotic forms for the other types of Bessel function follow straightforwardly from the above relations. For example, for large  , the modified Bessel functions become:

, the modified Bessel functions become:

Similarly, the last expressions are exact when  .

.

For small arguments  , they become:

, they become:

Properties

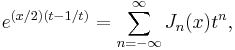

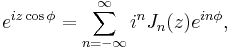

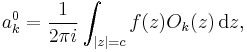

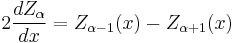

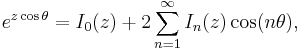

For integer order α = n, Jn is often defined via a Laurent series for a generating function:

an approach used by P. A. Hansen in 1843. (This can be generalized to non-integer order by contour integration or other methods.) Another important relation for integer orders is the Jacobi–Anger expansion:

and

which is used to expand a plane wave as a sum of cylindrical waves, or to find the Fourier series of a tone-modulated FM signal.

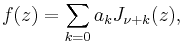

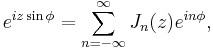

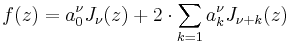

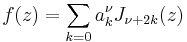

More generally, a series

is called Neumann expansion of ƒ. The coefficients for  have the explicit form

have the explicit form

where  is Neumann's polynomial.[28]

is Neumann's polynomial.[28]

Selected functions admit the special representation

with

due to the orthogonality relation

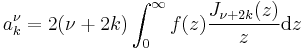

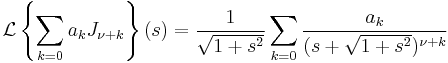

More generally, if ƒ has a branch-point near the origin of such a nature that  then

then

or

where  is ƒ's Laplace transform.[29]

is ƒ's Laplace transform.[29]

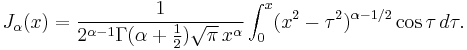

Another way to define the Bessel functions is the Poisson representation formula and the Mehler-Sonine formula:

where ν > −1/2 and z is a complex number.[30] This formula is useful especially when working with Fourier transforms.

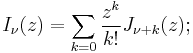

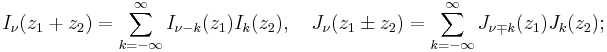

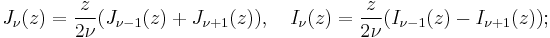

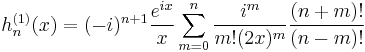

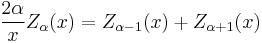

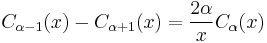

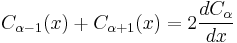

The functions Jα, Yα, Hα(1), and Hα(2) all satisfy the recurrence relations:

where Z denotes J, Y, H(1), or H(2). (These two identities are often combined, e.g. added or subtracted, to yield various other relations.) In this way, for example, one can compute Bessel functions of higher orders (or higher derivatives) given the values at lower orders (or lower derivatives). In particular, it follows that:

Modified Bessel functions follow similar relations :

and

The recurrence relation reads

where Cα denotes Iα or eαπiKα. These recurrence relations are useful for discrete diffusion problems.

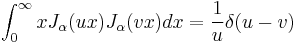

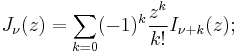

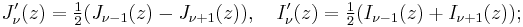

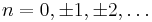

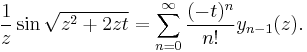

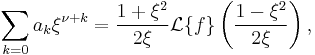

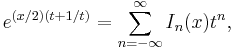

Because Bessel's equation becomes Hermitian (self-adjoint) if it is divided by x, the solutions must satisfy an orthogonality relationship for appropriate boundary conditions. In particular, it follows that:

where α > −1, δm,n is the Kronecker delta, and uα,m is the m-th zero of Jα(x). This orthogonality relation can then be used to extract the coefficients in the Fourier–Bessel series, where a function is expanded in the basis of the functions Jα(x uα,m) for fixed α and varying m.

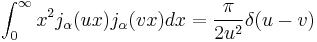

An analogous relationship for the spherical Bessel functions follows immediately:

Another orthogonality relation is the closure equation:[31]

for α > −1/2 and where δ is the Dirac delta function. This property is used to construct an arbitrary function from a series of Bessel functions by means of the Hankel transform. For the spherical Bessel functions the orthogonality relation is:

for α > −1.

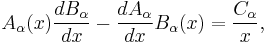

Another important property of Bessel's equations, which follows from Abel's identity, involves the Wronskian of the solutions:

where Aα and Bα are any two solutions of Bessel's equation, and Cα is a constant independent of x (which depends on α and on the particular Bessel functions considered). For example, if Aα = Jα and Bα = Yα, then Cα is 2/π. This also holds for the modified Bessel functions; for example, if Aα = Iα and Bα = Kα, then Cα is −1.

(There are a large number of other known integrals and identities that are not reproduced here, but which can be found in the references.)

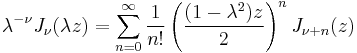

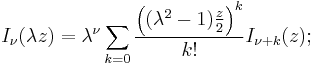

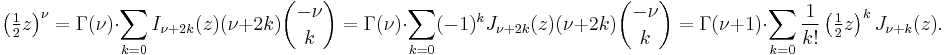

Multiplication theorem

The Bessel functions obey a multiplication theorem

where  and

and  may be taken as arbitrary complex numbers. A similar form may be given for

may be taken as arbitrary complex numbers. A similar form may be given for  and etc.[32] [33]

and etc.[32] [33]

Bourget's hypothesis

Bessel himself originally proved that for non-negative integers n, the equation Jn(x) = 0 has an infinite number of solutions in x.[34] When the functions Jn(x) are plotted on the same graph, though, none of the zeros seem to coincide for different values of n except for the zero at x = 0. This phenomenon is known as Bourget's hypothesis after the nineteenth century French mathematician who studied Bessel functions. Specifically it states that for any integers n ≥ 0 and m ≥ 1, the functions Jn(x) and Jn+m(x) have no common zeros other than the one at x = 0. The theorem was proved by Siegel in 1929.[35]

Selected identities

See also

- Bessel–Clifford function

- Bessel polynomials

- Propagator

- Fourier–Bessel series

- Hahn–Exton q-Bessel function

- Jackson q-Bessel function

- Struve function

- Kelvin functions

- Lommel functions

- Lommel polynomial

- Neumann polynomial

- Vibrations of a circular drum

- Wright generalized Bessel function

Notes

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 360, 9.1.10.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 358, 9.1.5.

- ^ Watson, p. 176

- ^ http://www.math.ohio-state.edu/~gerlach/math/BVtypset/node122.html

- ^ http://www.nbi.dk/~polesen/borel/node15.html

- ^ Arfken & Weber, exercise 11.1.17.

- ^ Szegö, G. Orthogonal Polynomials, 4th ed. Providence, RI: Amer. Math. Soc., 1975.

- ^ Watson, p. 178.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 358, 9.1.3, 9.1.4.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 358, 9.1.6.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 360, 9.1.25.

- ^ Watson, p. 178

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 375, 9.6.2, 9.6.10, 9.6.11.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 374, 9.6.1.

- ^ Watson, p. 181.

- ^ M.Kh.Khokonov. Cascade Processes of Energy Loss by Emission of Hard Photons, JETP, V.99, No.4, pp. 690-707 (2004). Derived from formulas sourced to I. S. Gradshteĭn and I. M. Ryzhik, Table of Integrals, Series, and Products (Fizmatgiz, Moscow, 1963; Academic, New York, 1980).

- ^ Referred to as such in: Teichroew, D. The Mixture of Normal Distributions with Different Variances, The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. Vol. 28, No. 2 (Jun., 1957), pp. 510–512

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 437, 10.1.1.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 439, 10.1.25, 10.1.26;

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 438, 10.1.11.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 438, 10.1.12;

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 439, 10.1.39.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 439, 10.1.23.

- ^ Hong Du, "Mie-scattering calculation," Applied Optics 43 (9), 1951–1956 (2004)

- ^ a b Arfken & Weber.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 377, 9.7.1;

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 378, 9.7.2;

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 363, 9.1.82 ff.

- ^ E. T. Whittaker, G. N. Watson, A course in modern Analysis p. 536

- ^ I.S. Gradshteyn (И.С. Градштейн), I.M. Ryzhik (И.М. Рыжик); Alan Jeffrey, Daniel Zwillinger, editors. Table of Integrals, Series, and Products, seventh edition. Academic Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-12-373637-6. Equation 8.411.10

- ^ Arfken & Weber, section 11.2

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 363, 9.1.74.

- ^ C. Truesdell, "On the Addition and Multiplication Theorems for the Special Functions", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Mathematics, (1950) pp.752–757.

- ^ F. Bessel, Untersuchung des Theils der planetarischen Störungen, Berlin Abhandlungen (1824), article 14.

- ^ Watson, pp. 484–5

- ^ See, for example, Lide DR. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics: a ready-reference book of chemical CRC Press, 2004, ISBN 0849304857, p. A-95

References

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1965), "Chapter 9", Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, New York: Dover, pp. 355, ISBN 978-0486612720, MR0167642, http://www.math.sfu.ca/~cbm/aands/page_355.htm See also chapter 10.

- Arfken, George B. and Hans J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 6th edition (Harcourt: San Diego, 2005). ISBN 0-12-059876-0.

- Bayin, S.S. Mathematical Methods in Science and Engineering, Wiley, 2006, Chapter 6.

- Bayin, S.S., Essentials of Mathematical Methods in Science and Engineering, Wiley, 2008, Chapter 11.

- Bowman, Frank Introduction to Bessel Functions (Dover: New York, 1958). ISBN 0-486-60462-4.

- G. Mie, "Beiträge zur Optik trüber Medien, speziell kolloidaler Metallösungen", Ann. Phys. Leipzig 25 (1908), p. 377.

- Olver, F. W. J.; Maximon, L. C. (2010), "Bessel function", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F. et al., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521192255, MR2723248, http://dlmf.nist.gov/10

- Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007), "Section 6.5. Bessel Functions of Integer Order", Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8, http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html#pg=274

- B Spain, M.G. Smith, Functions of mathematical physics, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, London, 1970. Chapter 9 deals with Bessel functions.

- N. M. Temme, Special Functions. An Introduction to the Classical Functions of Mathematical Physics, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, 1996. ISBN 0-471-11313-1. Chapter 9 deals with Bessel functions.

- Watson, G.N., A Treatise on the Theory of Bessel Functions, Second Edition, (1995) Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48391-3.

External links

- Lizorkin, P.I. (2001), "Bessel functions", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=b/b015840

- Karmazina, L.N.; Prudnikov, A.P. (2001), "Cylinder function", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=c/c027610

- Rozov, =N.Kh. (2001), "Bessel equation", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=B/b015830

- Wolfram function pages on Bessel J and Y functions, and modified Bessel I and K functions. Pages include formulas, function evaluators, and plotting calculators.

- Wolfram Mathworld – Bessel functions of the first kind

- Bessel functions Jν, Yν, Iν and Kν in Librow Function handbook.

![Y_n(x) =

\frac{1}{\pi} \int_0^\pi \sin(x \sin\theta - n\theta) \, d\theta

- \frac{1}{\pi} \int_0^\infty

\left[ e^{n t} %2B (-1)^n e^{-n t} \right]

e^{-x \sinh t} \, dt.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/41a54c45bdacb872e47e033074ff4688.png)

![K_{1/3} (\xi) = \sqrt{3}\, \int_0^\infty \, \exp \left[- \xi

\left(1%2B\frac{4x^2}{3}\right) \sqrt{1%2B\frac{x^2}{3}} \right] \ dx](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6a12a49bc1aeffcce198e75280dec85a.png)

![K_{2/3} (\xi) = \frac{1}{ \sqrt{3}} \,

\int_0^\infty \, \frac{3%2B2x^2}{\sqrt{1%2Bx^2/3}}

\exp \left[- \xi \left(1%2B\frac{4x^2}{3}\right) \sqrt{1%2B\frac{x^2}{3}} \right] \ dx](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b68918a0584b459afffdc928756ed54d.png)

![x^2 \frac{d^2 y}{dx^2} %2B 2x \frac{dy}{dx} %2B [x^2 - n(n%2B1)]y = 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/316a1e7b77811ba96493039cc95234cd.png)

![\begin{align}

J_{n%2B\frac 1 2}(x)=\sqrt{\frac 2 {\pi x}}\sum_{i=0}^\frac {n%2B1} 2 (-1)^{n-i} & \left[ \sin(x) \left(\frac 2 x\right)^{n-2i} \frac {(n-i)!}{i!} {-\frac 1 2 -i \choose n-2i} \right. \\

& \left.{} - \cos(x) \left(\frac 2 x\right)^{n%2B1-2i} \frac {(n-i)!}{i!} i {-\frac 1 2 -i \choose n-2i%2B1}\right],

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d34a546f6ab099afc7cdd79d03219931.png)

![x^2 \frac{d^2 y}{dx^2} %2B [x^2 - n (n%2B1)] y = 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0dc9509ffe5ae3661f508fe1752ba995.png)

![Y_\alpha(x) \approx \begin{cases}

\frac{2}{\pi} \left[ \ln (x/2) %2B \gamma \right] & \text{if } \alpha=0 \\ \\

-\frac{\Gamma(\alpha)}{\pi} \left( \frac{2}{x} \right) ^\alpha & \text{if } \alpha > 0

\end{cases}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7923ee757c2b36c60b5d09ae7200ee34.png)

![\left( \frac{d}{x dx} \right)^m \left[ x^\alpha Z_{\alpha} (x) \right] = x^{\alpha - m} Z_{\alpha - m} (x)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d1a58356b3bf0462c7c606ccac45de73.png)

![\left( \frac{d}{x dx} \right)^m \left[ \frac{Z_\alpha (x)}{x^\alpha} \right] = (-1)^m \frac{Z_{\alpha %2B m} (x)}{x^{\alpha %2B m}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f4090bd15fe15edf10d603afa749b2e0.png)

![\int_0^1 x J_\alpha(x u_{\alpha,m}) J_\alpha(x u_{\alpha,n}) dx

= \frac{\delta_{m,n}}{2} [J_{\alpha%2B1}(u_{\alpha,m})]^2

= \frac{\delta_{m,n}}{2} [J_{\alpha}'(u_{\alpha,m})]^2,\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cdb1e8ba98f7855eba9777024cce03fd.png)

![\int_0^1 x^2 j_\alpha(x u_{\alpha,m}) j_\alpha(x u_{\alpha,n}) dx

= \frac{\delta_{m,n}}{2} [j_{\alpha%2B1}(u_{\alpha,m})]^2\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/98df8d45fa6c659c53994ecde0481bbc.png)